Is A Creek Chub A Game Animal

Prairies are ecosystems considered office of the temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands biome by ecologists, based on similar temperate climates, moderate rainfall, and a composition of grasses, herbs, and shrubs, rather than copse, as the dominant vegetation type. Temperate grassland regions include the Pampas of Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay, and the steppe of Ukraine, Russia and Kazakhstan. Lands typically referred to as "prairie" tend to be in North America. The term encompasses the expanse referred to as the Interior Lowlands of Canada, the United states of america, and Mexico, which includes all of the Great Plains also every bit the wetter, hillier land to the e.

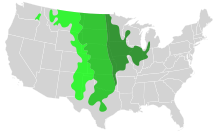

In the U.S., the area is constituted by most or all of u.s. of North Dakota, Due south Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma, and sizable parts of the states of Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, New United mexican states, Texas, Missouri, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Wisconsin, and western and southern Minnesota. The Palouse of Washington and the Central Valley of California are also prairies. The Canadian Prairies occupy vast areas of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. Prairies incorporate various lush flora and fauna, often contain rich soil maintained by biodiversity, with a temperate climate and a varied view.[1] [2]

Etymology [edit]

Guess regional types of prairie in the United States

According to Theodore Roosevelt:

We have taken into our language the give-and-take prairie, because when our backwoodsmen first reached the land [in the Midwest] and saw the swell natural meadows of long grass—sights unknown to the gloomy forests wherein they had ever dwelt—they knew not what to call them, and borrowed the term already in utilise amongst the French inhabitants.[3]

Prairie (pronounced [pʁɛʁi]) is the French word for "meadow"; the root is the Latin pratum (same meaning).

Formation [edit]

The formation of the North American Prairies started with the uplift of the Rocky Mountains most Alberta. The mountains created a rain shadow that resulted in lower precipitation rates downwind.[4]

The parent cloth of most prairie soil was distributed during the last glacial advance that began virtually 110,000 years ago. The glaciers expanding southward scraped the landscape, picking upward geologic cloth and leveling the terrain. As the glaciers retreated about 10,000 years ago, they deposited this fabric in the grade of till. Wind based loess deposits likewise form an important parent material for prairie soils.[5]

Tallgrass prairie evolved over tens of thousands of years with the disturbances of grazing and fire. Native ungulates such every bit bison, elk, and white-tailed deer roamed the expansive, diverse grasslands before European colonization of the Americas.[vi] For 10,000-20,000 years, native people used fire annually as a tool to assist in hunting, transportation, and safety.[vii] Evidence of ignition sources of burn in the tall grass prairie are overwhelmingly human being as opposed to lightning.[eight] Humans, and grazing animals, were active participants in the procedure of prairie formation and the establishment of the multifariousness of graminoid and forbs species. Fire has the event on prairies of removing trees, immigration dead plant affair, and irresolute the availability of certain nutrients in the soil from the ash produced. Fire kills the vascular tissue of trees, but non prairie species, as upward to 75% (depending on the species) of the total plant biomass is beneath the soil surface and will re-abound from its deep (upwards of xx feet[9]) roots. Without disturbance, trees will encroach on a grassland and cast shade, which suppresses the understory. Prairie and widely spaced oak trees evolved to coexist in the oak savanna ecosystem.[10]

Fertility [edit]

In spite of long recurrent droughts and occasional torrential rains, the grasslands of the Keen Plains were non subject to great soil erosion. The root systems of native prairie grasses firmly held the soil in place to prevent run-off of soil. When the institute died, the fungi and bacteria returned its nutrients to the soil. These deep roots also helped native prairie plants reach water in even the driest conditions. Native grasses suffer much less damage from dry out conditions than many farm crops currently grown.[11] [12]

Geographical regions [edit]

Prairie in North America is normally split into three groups: wet, mesic, and dry out.[thirteen] They are more often than not characterized by tallgrass prairie, mixed, or shortgrass prairie, depending on the quality of soil and rainfall.

Moisture [edit]

In wet prairies the soil is usually very moist, including during most of the growing season, because of poor water drainage. The resulting stagnant water is conducive to the formation of bogs and fens. Moisture prairies have first-class farming soil. The average precipitation is 10–xxx inches (250–760 mm) a yr.

Mesic [edit]

Mesic prairie has good drainage, but expert soil during the growing season. This type of prairie is the most often converted for agricultural usage; consequently, it is one of the virtually endangered types of prairie.

Dry [edit]

Wheatfield intersection in the Southern Saskatchewan prairies, Canada.

Dry prairie has somewhat moisture to very dry soil during the growing season because of good drainage in the soil. Often, this blazon of prairie can be institute on uplands or slopes. Dry soil usually doesn't go much vegetation due to lack of rain.[xiv] This is the ascendant biome in the Southern Canadian agricultural and climatic region known as Palliser's Triangle. In one case thought to be completely unarable, the Triangle is now 1 of the near important agronomical regions in Canada thanks to advances in irrigation technology. In add-on to its very loftier local importance to Canada, Palliser's Triangle is now also ane of the most important sources of wheat in the globe every bit a consequence of these improved methods of watering wheat fields (along with the rest of the Southern prairie provinces which besides grow wheat, canola and many other grains). Despite these advances in farming technology, the area is still very decumbent to extended periods of drought, which can be disastrous for the industry if it is significantly prolonged.[15] An infamous instance of this is the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, which also hit much of the U.s. Nifty Plains ecoregion, contributing profoundly to the Groovy Depression.[15]

Environmental history [edit]

Bison hunting [edit]

Nomadic hunting has been the primary human activity on the prairies for the majority of the archaeological record. This once included many now-extinct species of megafauna.

Afterward the other extinctions, the primary hunted animal on the prairies was the plains bison. Using loud noises and waving big signals, Native peoples would drive bison into fenced pens chosen buffalo pounds to exist killed with bows and arrows or spears, or drive them off a cliff (chosen a buffalo jump), to impale or injure the bison en masse. The introduction of the horse and the gun profoundly expanded the killing power of the plains Natives. This was followed by the policy of indiscriminate killing by European Americans and Canadians for both commercial reasons and to weaken the independence of plains Natives, and acquired a dramatic drib in bison numbers from millions to a few hundred in a century's fourth dimension, and almost acquired their extinction.

Farming and ranching [edit]

Prairie Homestead, Milepost 213 on I-29, Due south Dakota (May 2010).

The very dense soil plagued the first European settlers who were using wooden plows, which were more suitable for loose forest soil. On the prairie, the plows bounced around, and the soil stuck to them. This problem was solved in 1837 by an Illinois blacksmith named John Deere who developed a steel moldboard plow that was stronger and cutting the roots, making the fertile soils prepare for farming. Former grasslands are now among the most productive agricultural lands on Earth.[xvi]

The tallgrass prairie has been converted into one of the most intensive ingather producing areas in North America.[17] Less than one tenth of ane percent (<0.09%) of the original landcover of the tallgrass prairie biome remains.[18] States formerly with landcover in native tallgrass prairie such as Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Nebraska, and Missouri have become valued for their highly productive soils and are included in the Corn Belt. Every bit an example of this land use intensity, Illinois and Iowa rank 49th and 50th, out of 50 United states states, in full uncultivated country remaining.[19]

Drier shortgrass prairies were once used generally for open up-range ranching. But the development of barbed wire in the 1870s, and improved irrigation techniques, mean that this region has mostly been converted to cropland and minor fenced pasture as well.

Biofuels [edit]

Enquiry by David Tilman, ecologist at the University of Minnesota, suggests that "Biofuels made from high-diversity mixtures of prairie plants can reduce global warming by removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Fifty-fifty when grown on infertile soils, they can provide a substantial portion of global energy needs, and get out fertile country for food production."[20] Different corn and soybeans, which are both directly and indirectly major food crops, including livestock feed, prairie grasses are non used for human consumption. Prairie grasses can be grown in infertile soil, eliminating the cost of calculation nutrients to the soil. Tilman and his colleagues estimate that prairie grass biofuels would yield 51 percent more than free energy per acre than ethanol from corn grown on fertile land.[twenty] Some plants commonly used are lupine, big bluestem (turkey foot), blazing star, switchgrass, and prairie clover.

Preservation [edit]

Because rich and thick topsoil made the land well suited for agricultural use, only 1% of tallgrass prairie remains in the U.Due south. today.[21] Shortgrass prairie is more than abundant.

Significant preserved areas of prairie include:

- Alderville Blackness Oak Savanna; Rice Lake, Ontario[22]

- American Prairie, Phillips and Blaine counties, Montana

- Clymer Meadow Preserve, Hunt County, Texas

- Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park, Alberta and Saskatchewan

- Goose Lake Prairie Land Natural Area, Grundy Canton, Illinois

- Grasslands National Park, Saskatchewan

- Hoosier Prairie, Lake County, Indiana

- James Woodworth Prairie Preserve, a virgin prairie owned by Academy of Illinois, Glenview, Illinois[23]

- Jennings Environmental Educational activity Center, Pennsylvania

- Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park, Okeechobee County, Florida

- Konza Prairie, Manhattan, Kansas

- Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie, in Volition County, Illinois

- Mnoké Prairie, Indiana Dunes National Park, Porter, Indiana

- Nachusa Grasslands, a Nature Conservancy preserve near Franklin Grove, Illinois

- Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge, in Comanche County, Oklahoma

- Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge, Iowa

- Nine-Mile Prairie, Nebraska

- Ojibway prairie in Windsor, Ontario.[24]

- Paynes Prairie Preserve Land Park, Alachua Canton, Florida

- Richard Bell State Recreation Expanse, in Kenosha County, Wisconsin

- Russell R. Kirt Prairie, Higher of DuPage, Illinois[25]

- Tallgrass Aspen Parkland, Manitoba & Minnesota

- Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, Kansas

- Tallgrass Prairie Preserve 32,000 acres (130 km2), Oklahoma

- University of Wisconsin–Madison Arboretum, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Wisconsin

- Zumwalt Prairie, Wallowa County, Oregon

Virgin prairies [edit]

Virgin prairie refers to prairie country that has never been plowed. Small virgin prairies exist in the American Midwestern states and in Canada. Restored prairie refers to a prairie that has been reseeded after plowing or other disturbance.

Prairie garden [edit]

A prairie garden is a garden primarily consisting of plants from a prairie.

Physiography [edit]

The originally treeless prairies of the upper Mississippi basin began in Indiana, and extended westward and north-westward, until they merged with the drier region known as the Groovy Plains. An due east extension of the aforementioned region, originally tree-covered, extended to key Ohio. Thus, the prairies generally lie between the Ohio and Missouri rivers on the south and the Bully Lakes on the north. The prairies are a contribution of the glacial menses. They consist for the nearly part of glacial drift, deposited unconformably on an underlying rock surface of moderate or small relief. Here, the rocks are an extension of the same stratified Palaeozoic formations already described as occurring in the Appalachian region and around the Great Lakes. They are usually fine-textured limestones and shales, lying horizontal. The moderate or minor relief that they were given past mature preglacial erosion is now cached nether the drift.

View of sand dunes and vegetation at Fossil Lake, with the Christmas Valley Sand Dunes Feb. 21, 2017.

The greatest area of the prairies, from Indiana to North Dakota, consists of till plains, that is, sheets of unstratified drift. These plains are 30, 50 or fifty-fifty 100 ft (up to thirty yard) thick covering the underlying rock surface for thousands of square miles except where postglacial stream erosion has locally laid information technology blank. The plains take an extraordinarily fifty-fifty surface. The till is presumably made in office of preglacial soils, simply it is more than largely composed of rock waste mechanically transported past the creeping ice sheets. Although the crystalline rocks from Canada and some of the more resistant stratified rocks due south of the Great Lakes occur as boulders and stones, a great function of the till has been crushed and ground to a clayey texture. The till plains, although sweeping in broad swells of slowly irresolute altitude, oft appear level to the middle with a view stretching to the horizon. Hither and there, faint depressions occur, occupied by marshy sloughs, or floored with a rich blackness soil of postglacial origin. It is thus by sub-glacial aggradation that the prairies accept been levelled up to a shine surface, in contrast to the higher and not-glaciated hilly country but to the s.

The great ice sheets formed concluding moraines around their border at various end stages. Notwithstanding, the morainic belts are of small relief in comparing to the not bad area of the water ice. They ascension gently from the till plains to a peak of 50, 100 or more feet. They may be one, ii or 3 miles (5 km) broad and their hilly surface, dotted over with boulders, contains many modest lakes in basins or hollows, instead of streams in valleys. The morainic belts are arranged in groups of concentric loops, convex southward, because the ice sheets advanced in lobes forth the lowlands of the Great Lakes. Neighboring morainic loops bring together each other in re-entrants (due north-pointing cusps), where two adjacent glacial lobes came together and formed their moraines in largest volume. The moraines are of too pocket-sized relief to exist shown on any maps except of the largest calibration. Small every bit they are, they are the chief relief of the prairie states, and, in association with the about imperceptible slopes of the till plains, they make up one's mind the grade of many streams and rivers, which as a whole are consequent upon the surface form of the glacial deposits.

The complexity of the glacial period and its subdivision into several glacial epochs, separated by interglacial epochs of considerable length (certainly longer than the postglacial epoch) has a structural result in the superposition of successive till sheets, alternating with non-glacial deposits. It also has a physiographic outcome in the very different corporeality of normal postglacial erosion suffered by the different parts of the glacial deposits. The southernmost drift sheets, every bit in southern Iowa and northern Missouri, have lost their initially plain surface and are now maturely dissected into gracefully rolling forms. Here, the valleys of even the small-scale streams are well opened and graded, and marshes and lakes are rare. These sheets are of early Pleistocene origin. Nearer the Peachy Lakes, the till sheets are trenched only by the narrow valleys of the big streams. Marshy sloughs notwithstanding occupy the faint depressions in the till plains and the associated moraines have abundant small-scale lakes in their undrained hollows. These drift sheets are of belatedly Pleistocene origin.

When the water ice sheets extended to the state sloping southward to the Ohio River, Mississippi River and Missouri River, the drift-laden streams flowed freely abroad from the ice border. Equally the streams escaped from their subglacial channels, they spread into broader channels and deposited some of their load, and thus aggraded their courses. Local sheets or aprons of gravel and sand are spread more or less abundantly along the outer side of the morainic belts. Long trains of gravel and sands clog the valleys that pb southward from the glaciated to the non-glaciated area. After, when the ice retreated farther and the unloaded streams returned to their earlier degrading habit, they more or less completely scoured out the valley deposits, the remains of which are now seen in terraces on either side of the nowadays inundation plains.

When the ice of the last glacial epoch had retreated then far that its front end border lay on a northward slope, belonging to the drainage area of the Bully Lakes, bodies of h2o accumulated in front end of the ice margin, forming glacio-marginal lakes. The lakes were pocket-size at get-go, and each had its own outlet at the lowest low of land to the s. As the ice melted further dorsum, neighboring lakes became confluent at the level of the lowest outlet of the grouping. The outflowing streams grew in the same proportion and eroded a broad channel across the height of land and far downwards stream, while the lake waters built sand reefs or carved shore cliffs forth their margin, and laid down sheets of dirt on their floors. All of these features are hands recognized in the prairie region. The nowadays site of Chicago was determined by an Indian portage or carry across the low divide between Lake Michigan and the headwaters of the Illinois River. This divide lies on the flooring of the old outlet channel of the glacial Lake Michigan. Corresponding outlets are known for Lake Erie, Lake Huron, and Lake Superior. A very large sheet of water, named Lake Agassiz, in one case overspread a broad till plain in northern Minnesota and North Dakota. The outlet of this glacial lake, chosen river Warren, eroded a large channel in which the Minnesota River evident today. The Red River of the N flows northward through a plain formerly covered past Lake Agassiz.

Certain extraordinary features were produced when the retreat of the ice sheet had progressed so far as to open an eastward outlet for the marginal lakes. This outlet occurred forth the depression between the due north gradient of the Appalachian plateau in westward-key New York and the southward slope of the melting ice canvass. When this east outlet came to be lower than the s-westward outlet beyond the height of land to the Ohio or Mississippi river, the discharge of the marginal lakes was changed from the Mississippi system to the Hudson system. Many well-defined channels, cutting across the northward-sloping spurs of the plateau in the neighborhood of Syracuse, New York, mark the temporary paths of the ice-bordered outlet river. Successive channels are establish at lower and lower levels on the plateau slope, indicating the successive courses taken by the lake outlet as the ice melted farther and farther back. On some of these channels, deep gorges were eroded heading in temporary cataracts which exceeded Niagara in height but not in breadth. The pools excavated by the plunging waters at the head of the gorges are now occupied past little lakes. The near significant stage in this series of changes occurred when the glacio-marginal lake waters were lowered so that the long escarpment of Niagara limestone was laid blank in western New York. The previously confluent waters were and then divided into 2 lakes. The higher one, Lake Erie, supplied the outflowing Niagara River, which poured its waters down the escarpment to the lower, Lake Ontario. This gave rise to Niagara Falls. Lake Ontario's outlet for a fourth dimension ran down the Mohawk Valley to the Hudson River. At this college elevation, information technology was known as Lake Iroquois. When the ice melted from the northeastern terminate of the lake, it dropped to a lower level, and drained through the St. Lawrence area. This created a lower base level for the Niagara River, increasing its erosive chapters.

In sure districts, the subglacial till was non spread out in a shine plain, only accumulated in elliptical mounds, 100–200 anxiety. loftier and 0.5 to 1 mile (0.80 to 1.61 kilometres) long with axes parallel to the direction of the ice motion as indicated past striae on the underlying stone floor. These hills are known by the Irish proper name, drumlins, used for similar hills in north-western Ireland. The most remarkable groups of drumlins occur in western New York, where their number is estimated at over 6,000, and in southern Wisconsin, where information technology is placed at 5,000. They completely dominate the topography of their districts.

A curious deposit of an impalpably fine and unstratified silt, known past the German proper noun bess (or loess), lies on the older drift sheets near the larger river courses of the upper Mississippi basin. It attains a thickness of twenty ft (6.ane m) or more than about the rivers and gradually fades away at a distance of ten or more miles (16 or more km) on either side. It contains land shells, and hence cannot be attributed to marine or lacustrine submergence. The best explanation is that, during certain phases of the glacial flow, it was carried as grit by the winds from the flood plains of aggrading rivers, and slowly deposited on the neighboring grass-covered plains. The glacial and eolian origin of this sediment is evidenced by the angularity of its grains (a bank of it will stand without slumping for years), whereas, if it had been transported significantly by water, the grains would accept been rounded and polished. Loess is parent material for an extremely fertile, but droughty soil.

Southwestern Wisconsin and parts of the adjacent states of Illinois, Iowa, and Minnesota are known equally the driftless zone, because, although bordered by drift sheets and moraines, information technology is free from glacial deposits. It must therefore have been a sort of oasis, when the ice sheets from the north advanced past it on the east and west, and joined around its southern edge. The reason for this exemption from glaciation is the converse of that for the southward convexity of the morainic loops. For while they marking the paths of greatest glacial advance along lowland troughs (lake basins), the driftless zone is a commune protected from water ice invasion by reason of the obstruction which the highlands of northern Wisconsin and Michigan (office of the Superior upland) offered to glacial advance.

The class of the upper Mississippi River is largely consequent upon glacial deposits. Its sources are in the morainic lakes in northern Minnesota. The drift deposits thereabouts are so heavy that the present divides between the drainage basins of Hudson Bay, Lake Superior, and the Gulf of Mexico evidently stand in no very definite relation to the preglacial divides. The grade of the Mississippi through Minnesota is largely guided past the form of the drift cover. Several rapids and the Saint Anthony Falls (determining the site of Minneapolis) are signs of immaturity, resulting from superposition through the migrate on the under rock. Further south, as far as the entrance of the Ohio River, the Mississippi follows a rock-walled valley 300 to 400 ft (91 to 122 m) deep, with a flood-apparently 2 to four mi (3.two to 6.4 km) wide. This valley seems to represent the path of an enlarged early-glacial Mississippi, when much precipitation that is today discharged to Hudson Bay and the Gulf of St Lawrence was delivered to the Gulf of Mexico, for the curves of the present river are of distinctly smaller radii than the curves of the valley. Lake Pepin (30 mi [48 km] below St. Paul), a picturesque expansion of the river across its flood-plain, is due to the aggradation of the valley floor where the Chippewa River, coming from the northeast, brought an overload of fluvio-glacial drift. Hence, fifty-fifty the father of waters, similar so many other rivers in the Northern states, owes many of its features more or less directly to glacial action.

The fertility of the prairies is a natural upshot of their origin. During the mechanical transportation of the till, no vegetation was present to remove the minerals essential to found growth, as is the case in the soils of normally weathered and dissected peneplains. The soil is similar to the Appalachian piedmont which though not exhausted by the primeval wood cover, are by no means so rich as the till sheets of the prairies. Moreover, whatever the rocky understructure, the till soil has been averaged by a thorough mechanical mixture of rock grindings. Hence, the prairies are continuously fertile for scores of miles together. The truthful prairies were once covered with a rich growth of natural grass and annual flowering plants, but today, they are covered with farms.

See too [edit]

References [edit]

- ^ Alford, Aaron L.; Hellgren, Eric C.; Limb, Ryan; Engle, David M. (May 19, 2012). "Experimental tree removal in tallgrass prairie: variable responses of flora and animate being along a woody cover gradient". Ecological Applications. 22 (3): 947–958. doi:10.1890/x-1288.1. PMID 22645823 – via Wiley Online Library.

- ^ Agnew, William; Uresk, Daniel Due west.; Hansen, Richard M. (March 1986). "Flora and creature associated with prairie domestic dog colonies and next ungrazed mixed-grass prairie in western Due south Dakota" (PDF). Journal of Range Management. 39 (2): 135–139. doi:ten.2307/3899285. hdl:10150/645493. JSTOR 3899285 – via Us Department of Agriculture.

- ^ Roosevelt, Theodore (1889). The Winning of the Due west: Volume I. New York and London: K. P. Putnam'due south Sons. p. 34.

- ^ "Eastward Declension". www.atmos.washington.edu . Retrieved 2018-06-12 .

- ^ Pigsty, F.D.; 1000. Nielsen (1968). "Soil genesis under prairie". Proceedings of a Symposium on Prairie and Prairie Restoration.

- ^ Dinsmore, James and Muller, Marking. (Illustrator) A Country And then Full of Game: The Story of Wild fauna in Iowa Burr Oak Series. Apr 1994.

- ^ William J. McShea (Editor), William M. Healy (Editor) Oak Forest Ecosystems: Ecology and Direction for Wildlife The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1 edition (October 21, 2003)

- ^ Abrams, Marc D. Native Americans as agile and passive promoters of mast and fruit trees in the eastern USA The Holocene, Vol. xviii, No. 7, 1123-1137 (2008)

- ^ Weaver, J. Eastward. (1968). Prairie Plants and Their Environment. University of Nebraska.

- ^ Thompson, Janette R. Prairies, Forests, and Wetlands: The Restoration of Natural Mural Communities in Iowa Burr Oak Series. University Of Iowa Printing; 1 edition (June 1, 1992)

- ^ Keyser, Pat (2012-08-02). "Drought and Native Grasses". The University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture. Retrieved 2018-08-02 .

- ^ Taylor, Ciji (2013-06-03). "Native warm-season grasses weather drought, provide many other do good". southeastfarmpress.com. Southeast FarmPress. Retrieved 2018-08-02 .

- ^ "Prairie Types Guide by Prairie Frontier". www.prairiefrontier.com.

- ^ "Drought: A Paleo Perspective – 20th Century Drought". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved April 5, 2009.

- ^ a b "Drought in Palliser's Triangle". Retrieved June sixteen, 2015.

- ^ Graham, Linda E.; Graham, James 1000.; Wilcox, Lee Warren (2003). Found Biology. Prentice Hall. p. 26. ISBN978-0-13-030371-4.

- ^ Dáil, Paula vW (2015-01-28). Hard Living in America'due south Heartland: Rural Poverty in the 21st Century Midwest. McFarland. ISBN978-1-4766-1838-8.

- ^ Carl Kurtz. Iowa's Wild Places: An Exploration With Carl Kurtz (Iowa Heritage Collection) Iowa Land Printing; 1st edition (July thirty, 1996)

- ^ Dáil, Paula vW (2015-01-28). Hard Living in America's Heartland: Rural Poverty in the 21st Century Midwest. McFarland. ISBN978-1-4766-1838-eight.

- ^ a b David Tilman. "Mixed Prairie Grasses Better Source of Biofuel Than Corn Ethanol and Soybean Biodiesel". National Science Foundation (NSF). Retrieved December 7, 2006.

- ^ Robison, Roy; Donald B. White; Mary H. Meyer (1995). "Plants in Prairie Communities". Academy of Minnesota. Archived from the original on four April 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ "Alderville Start Nation Black Oak Savanna". www.aldervillesavanna.ca.

- ^ "James Woodworth Prairie Preserve". Academy of Illinois.

- ^ "Ojibway Prairie Complex - Parks & Recreation - City of Windsor". www.ojibway.ca.

- ^ "Russell R. Kirt Prairie". cod.edu.

External links [edit]

- The Prairie Enthusiasts – grassland protection and restoration in the upper Midwest

- Prairie Plains Resources Found

- The Native Prairies Association of Texas

- Importance of burn within the prairie

- Missouri Prairie Foundation

- America'due south Grasslands Documentary produced past Prairie Public Television set

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prairie

Posted by: wallaceborceir.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Is A Creek Chub A Game Animal"

Post a Comment